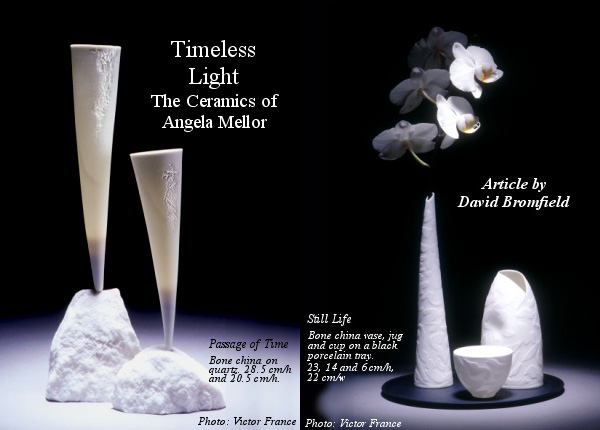

“Timeless Light: The Ceramics of Angela Mellor,” David Bromfield

Glacial Light I. Bone china and paperclay. 8.5 x 13, 11 x 19, 7 x 10.5 cm. Photo: Isamu Sawa.

FROM THE FOUNDATION OF MODERN DESIGN, natural forms have provided an antidote to industrial banalities and the loss of craft traditions. The notion of nature, in one guise or another, still plays a role in the work of most ceramic artists. Rather than invest they shamelessly borrow decorative designs and vessel shapes from flora and fauna. This need not be a bad thing. Even after a century and a half nature remains prolific. Yet natural form can be reduced to a convenient cliché in a second.

It is no easy matter to invent new forms, even to renew the old ones, yet it is unavoidable. The creation of shapes whose absolute, undeniable presence sings out to eye remains the primary task for ceramics as an art form. To achieve this, finesse, patina, surface, glazes, all must take second place to the ability to make objects with an aura so resilient that they stand out anywhere, not just in the glamorous sterility of the show case. They must, at least, rival the roses that will some day be placed next to them.

So many artists have abandoned the struggle between form and finesse entirely in favour of finesse. For them, especially natural form has become little more than an excuse to manifest an overwhelming technical competence. In the process, which is their process, nature expires parodied and smothered, living their works lifeless, with little appeal to the senses.

As a ceramicist, Angela Mellor's greatest achievement is the rigorous maintenance of her good relations with nature. In setting out to rival the presence of natural forms with her own work, she has made nature a congenial collaborator, ever ready to prompt and renew creative tension.

She has borrowed from natural forms, but her great passion is for the landscape and the processes which shape it and lend it form, folded rocks and crystalline light which could never provide a single template. It is the tide tossed textures of coral, driftwood, shells and stones found on the beach which attract her. Each caresses and modulates the light in different ways, clotting , condensing and trapping it in memory of its own, slow shapeshifting by wind and weather.

Glacial Light, the name of one series of Mellor's bowls, sums up her ambitions to rival such artefacts of nature, a work glowing with the presence of rocks and shells in shards of ice tumbled, slowly through rock for millennia. Like other works these pieces catch light in their thin shells so that it leaks infinitely slowly from an irregular fragile lip. The crumbling circlet of fragile indentations just below the top edge of each bowl emphasises this crisp, solid luminosity, so that it seems to have been trapped there forever. The unique presence of the Glacial Light series is not finessed from some flower or shell. It is established directly between the peerless white china, pure light and the passage of time.

This brilliance was not achieved without considerable research and reflection, first in her undergraduate studies at the University of Tasmania and recently in her Masters degree at Monash University, Melbourne (1998‑1999). Mellor began with an idea of light as substance and of a material so translucent that once shaped it would seem to hover forever on the edge of time, a second before the end of the world.

Sake Set. Bone china jug and five cups on black porcelain tray. 18 cm/h x 25 cm/w. Photo: Victor France.

She took some time testing to find the right clay. Commercial porcelain would not do. Nor did her experiments with blue pate de verre bases for some pieces, although attractive, hold the light in the way she wished. Eventually, she settled for a bone china mix1 pioneered by Dr Owen Rye, which required the addition of paper clay to stiffen each shape through the firing process. Experiments with various shapes, including a tea bowl, had shown that the range of forms suitable for this work was quite limited by her aspirations for it. There was, in other words, a natural series of possibilities.

Of course, light could have been engaged by a variety of glazes and this would have permitted stronger, thicker clay forms. Mellor rejected this possibility early in her research. it would not have solved the problems of translucency and fragility – the tell tale signs of time and presence in nature. More importantly glazes are always, in some sense, cosmetic. They continually tempt the artist to finesse inadequate or dull forms. Even the most lucid glaze must suggest the triumph of artifice over the natural.

Mellor’s early bowl experiments used the shape of the Datura flower to form a metal template. She occasionally cast fragments of coral and other materials from the landscape to study their surface and structure. Most of her reflection on the fragility of natural forms was and is conducted through photographs of textures and shapes large and small found in the landscape, the shadow of a leaf or the surface of an eroded rocky cliff.

Her most significant early experiment in the relation of light to such forms was a series of etched lampshades and related vessels made in 1997. Silhouettes of leaves and vines were painted onto the fired piece and the background was sponged away so that the design appeared in relief. This method enabled very careful control over the thickness and translucency of the china so that light emanating from its centre could be given specific quality.

Beautiful as they are these shapes remain self evidently artificial, a theatrical way station towards the self sufficiency, the natural presence of Mellor’s recent bone china pieces. The next inevitable step was a struggle to step back, to give her forms a chance to grow in terms of their own fragility. First came experiments with pieces of paper clay shaped from natural forms and embedded into the side of vessels such as Coral Bowl or Flute, both made in 1997, so as to burn out, leaving a trace like the fossil imprints of leaves and insects still discovered between layers of coal and shale as they are broken for burning.

This burning out of the motif is evidently much more than a technical convenience. It comes close to a natural process of form creation, exact only in its own terms but delightful because of the sensual dialogue it opens up between the viewer and the object. The sense of change embodied in the form, of the contribution time and decay have made to its ultimate shape establishes the presence of the object in the natural world. Sight and touch delight in these traces of change in the same way they would in a pebble worn smooth by endless tides. The ability to achieve a strong autonomous presence remains the most significant possibility for ceramics as an art form.

The next step for Mellor was a series of experiments with bowl shapes and other appropriate forms. She developed and refined a slip casting technique and in doing so moved her bowl forms further away from any references to plant forms. One apparent exception to this appeared in a substantial series of elongated cone like pieces inspired by her experience of the stalactites and stalagmites of the limestone caves at Yallingup and elsewhere in the south of Western Australia. It is only an apparent exception. Not all natural processes are the same. These limestone formations are built up very slowly by the dissolution and redeposition of limestone by water which constantly covers them so as to form a glowing crystalline light trap. Such mineral forms have a direct relationship to Mellor’s own interest in light and time. She named one set of two cone pieces Passage of Time 1 (2000).

Glacial Light. Bone china with paperclay inlay. 7 x 10.5 cm. Photo: Isamu Sawa.

As Mellor's forms achieved ever stronger presence, their sculptural qualities slowly came to the fore. She began to group bowls together so that they had a similar presence to clusters of sponges or corals whose shape and proportion had grown up in relation of each other. Both Glacial Light I and II work in this way. The shapes of three bowls in Glacial Light I amplify each others presence but also suggest that they may be part of an infinite natural series. The cone shapes easily formed groups that echoed the caves that inspired them.

Colour, when it occasionally appears, is also a sculptural element in Mellor's work. Given her creative aims colour must always appear to have come into being as a necessary element of the growth of the form, an aspect of its presence locked into its light. It can never be a decorative after thought. In the set of three Coral Vessels a faintly variegated tinge of sea green seems to have set solid in bone china. Its slight striations follow the form exactly as if they had been worn into place. Mellor takes care never to lose their translucency.

The dilemma of how to support craftwork with a primarily sculptural presence is almost perennial. Mellor's pieces might well be best presented with no support but the landscape, as discoveries in the tide line folds of a coastal reef, the cones attached to rocks and the bowls submerged in rocks shedding a crystalline translucent light through the ever moving water. This may not be practical, but shapes carved in light will always need to float or fly. Any base must contradict this impulse, the cone shapes present this problem most clearly since their forms are often predicated on growth downwards from a rocky ceiling.

Mellor has two current solutions to this problem. For many forms, especially the cones, she uses pieces of brilliant white quartz crystal from a quarry in Sydney. Others, for instance a set of small sake cups or a bone china jug and cups, she presents surrounded by black paper or on black tray. These extremes of light and dark both allow the forms a vivacious existence in terms of the light that they capture and release rather than as mere curious shapes, shipwrecked in a display case.

Light is always at the centre of Mellor's work. Because of this she has been able to free her practice from the dilemmas of fashionable technical rhetoric while maintaining an enviable tension between her creative project and carefully disciplined technical innovation. Her works have an extraordinary independent presence. This is a rare and remarkable achievement.

Reference:

1. The bone china recipe used is 30 parts kaolin, bone ash 45, potash feldspar 22.8 and silica 2.2. To this is added 2g dispex and 1g sodium silicate and 600ml water per dry kilo weight.

David Bromfield is an art critic for the West Australian. Angela Mellor has had work accepted for the 1st Biennale, Korea, September 2001 and Monet in Japan, Canberra, and Perth, 2001. She may be contacted through her website: www.angelamellor.com.

< Back to Press articles | “Illuminated Ceramic Objects,” Angela Mellor >